The Nature of Productivity: Charles Darwin’s Path to Peace and Progress

Learn how Darwin structured his days for deep work and restoration—and how you can design your routine that encourages focus, creativity, and wellbeing.

Now that we’re well into spring and summer is nearly here, I’ve been reflecting on how healing it feels to walk through the greenery of my local park. Just a short time in nature clears my head—it’s like waking up after a long winter.

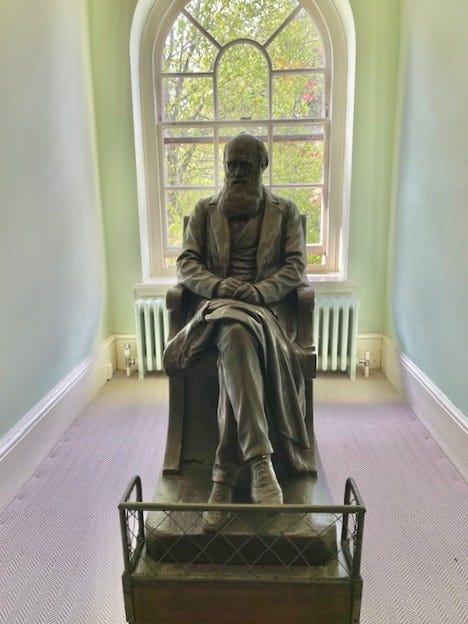

It reminds me of an inspiring visit I once took to Down House in Kent, UK, the home of Charles Darwin. This quiet estate, where Darwin wrote On the Origin of Species, wasn’t just a place of great scientific discovery—it was also a personal retreat where he designed a routine to support his mental and physical health.

Darwin battled chronic illness for most of his life, yet his gentle daily habits—especially time in nature, regular walks, focused work blocks, and family connection—allowed him to produce groundbreaking work.

In this post, I’ll share Darwin’s challenges, what his routine looked like, and how his lifestyle choices supported his work. We’ll explore how some of his 19th-century practices are backed by modern science—and how you might adapt them to your own routine to help improve focus, reduce anxiety, and feel more grounded in your day.

Who was Charles Darwin?

Charles Darwin was born on 12 February 1809. Darwin published the scientific theory of natural selection from the joint presentation of his and Alfred Russel Wallace’s research to the Linnean Society in 1858. The following year, Darwin published ‘On the Origin of Species’ (the title in full ‘On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life’)1. These works describe natural selection as the process by which species that are better adapted to their environment tend to survive and produce more offspring; it is now regarded as the significant mechanism that causes evolution.

Life before Down House

Charles Darwin was born into a prominent family, being the grandson of influential figures, Josiah Wedgewood and Erasmus Darwin. Charles Darwin studied at the University of Edinburgh Medical School, but his passion for natural history overshadowed his medical studies. This led him to Christ’s College, Cambridge, where he continued to focus on natural science under the mentorship of Professor John Stevens Henslow, despite Darwin’s intention to study to be an Anglican country parson23.

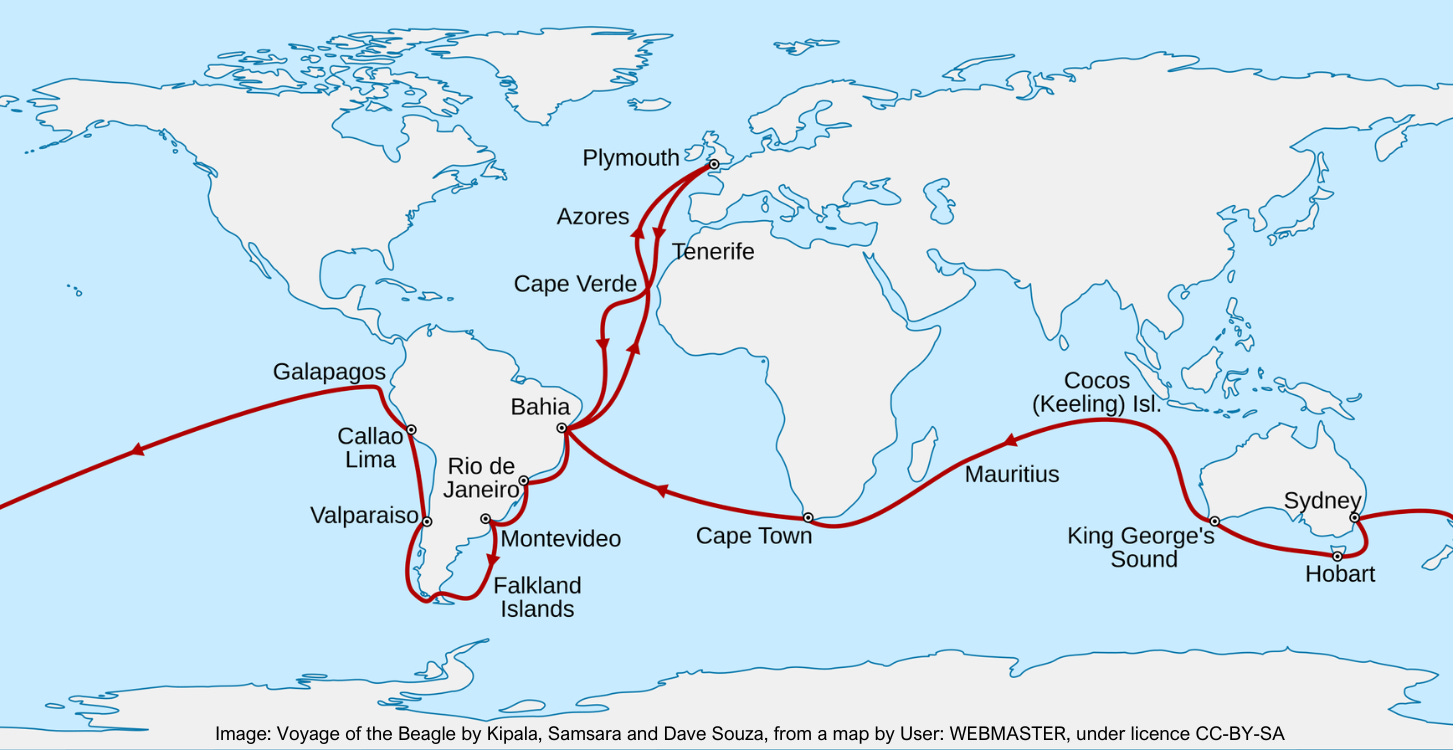

In 1831, at the age of 22, Darwin embarked on a pivotal voyage aboard the HMS Beagle, where he explored various environments and collected specimens, gaining insights that would influence his later work on evolution. After returning to London in 1837, health issues prompted him to seek a quieter life, during which he began to develop his theory of evolution, despite the unknown causes of his maladies.

Illness and Unconventional Treatments

It is incredible to consider how successful Darwin became despite his chronic illness. Darwin had health problems even before the Beagle voyages and complained of heart palpitations while waiting in port before setting sail. He continued to suffer from many severe symptoms, leaving him debilitated for long periods with an uncommon combination of symptoms, including heart palpitations, stomach pains, vomiting, headaches, severe tiredness, eczema, insomnia, and anxiety, leading to speculation to this day regarding the causes4. The suggestions for the cause of his illness include PTSD5, MELAS (mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes)6, Chagas disease7, psychosomatic disease, Lupus erythematosus8, chronic fatigue syndrome9, and more. It is possible that there was a genetic component to Darwin’s illness, with his mother Susannah also suffering from gastric disease during her lifetime. She had a history of sickness and died at the age of 52 of a sudden, severe abdominal illness, possibly stomach cancer or acute hemorrhagic peritonitis, similar to that of her maternal uncle10.

Charles Darwin had no success with conventional treatments. In 1849, Darwin, after suffering from a bout of prolonged vomiting, followed the advice of his friend Captain Sulivan and cousin William Darwin Fox to seek treatment at Dr. James Gully's Water Cure Establishment in Malvern, Worcestershire. Darwin began a two-month water therapy trial, which included getting up early, cold footbaths, showers, strict dieting, and regular walks. Diagnosed with nervous dyspepsia, Darwin found the demanding regimen enjoyable and vigorous, helping him avoid feelings of guilt about not working. His treatment continued from March until June, after which he maintained the diet and water therapy at home, aided by his butler. At home, he implemented a structured routine that involved early rising and physical exercise, including walks on the newly constructed Sandwalk on his property {2,3}.

In 1856, Darwin began publishing his evolutionary theory; however, by March 1857, his health had declined, limiting his work hours. Seeking treatment from Dr. Edward Wickstead Lane at a hydropathic facility in Surrey proved beneficial, leading to significant improvements. Throughout 1857 and 1858, he returned multiple times while continuing his work on "On the Origin of Species," despite facing health challenges.

In June 1858, Darwin received a letter from Alfred Russel Wallace, who had outlined a similar theory of evolution by natural selection, which put pressure on Darwin to publish quickly. Darwin, a man of extraordinary moral character, felt obliged to act honourably and, well aware of the consequences, told renowned scientist Charles Lyell that he would submit Wallace's work to a journal for publication.

Darwin faced stress from potential negative reviews and sought treatment again in October, encountering various health issues, but reported feeling better towards the end of his stay. He returned home to Down House and continued to manage his fluctuating health.

Darwin’s Routine at Down House

The following is from Francis Darwin's reminiscences of his father. It summarized a typical day in Darwin's middle and later years when he had developed a routine that seldom changed, even when visitors were in the house. Adapted from Charles Darwin: A Companion by R.B. Freeman, accessed on The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online.

7 a.m. Rose and took a short walk.

7:45 a.m. Breakfast alone

8–9:30 a.m. Worked in his study; he considered this his best working time.

9:30–10:30 a.m.Went to drawing-room and read his letters, followed by reading aloud of family letters.

10:30 a.m.–12 p.m. Returned to his study, which period he considered the end of his working day.

12 noon Walk, starting with a visit to his greenhouse, then round the Sandwalk, the number of times depending on his health, usually alone, sometimes with his children, or with a dog.

12:45 p.m. Lunch with whole family, which was his main meal of the day. After lunch read The Times and answered his letters.

3 p.m. Rested in his bedroom on the sofa and smoked a cigarette, listened to a novel or other light literature read by ED [Emma Darwin, his wife].

4 p.m. Walked, usually round the Sandwalk, sometimes farther afield and sometimes in company.

4:30–5:30 p.m. Worked in his study, clearing up matters of the day.

6 p.m. Rested again in bedroom with ED reading aloud.

7.30 p.m. Light high tea while the family dined. In later years, he never stayed in the dining room with the men, but retired to the drawing-room with the ladies. If no guests were present, he played two games of backgammon with ED, usually followed by reading to himself, then ED played the piano, followed by reading aloud.

10 p.m.Left the drawing-room and usually in bed by 10:30, but slept badly.

Even when guests were present, half an hour of conversation at a time was all that he could stand, because it exhausted him.

The time Darwin spent doing work—reading, theorizing, writing, and experimenting—consisted of about 4 to 5 hours a day. However, you could add an extra hour or so of thinking time on his walks around the grounds.

Despite his routine and achieving numerous accomplishments in scientific theorising and experimentation, Darwin had some bad days. At the very least, he was known to have relatable off days, where he was too ill, anxious, or annoyed to work. The online Darwin Correspondence project has compiled quotes from his correspondence of his ‘bad days’.11 For example, Darwin is quoted as saying in a letter to his friend Charles Lyell ‘But I am very poorly today and very stupid and hate everybody and everything.’ 12

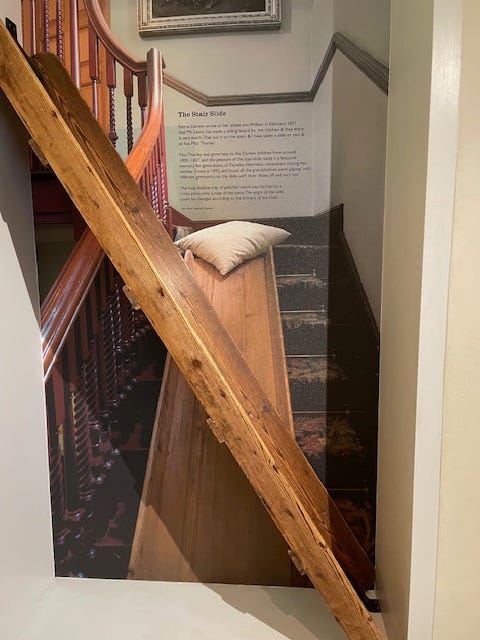

The Sandwalk

Key to his recovery, in 1846, Charles Darwin rented a 1.5-acre strip of land near Down House and named it Sandwalk Wood. Darwin ordered the construction of a gravel path known as the "Sandwalk" to be created around the outer edge of the wood, with a wooden summerhouse built at one end of the path. In 1874, Darwin exchanged a piece of pasture land with Sir John Lubbock's son, gaining full ownership of Sandwalk Wood. An old shaw, a small wood, with oak trees shaded one side, and the other looked over a hedge to a picturesque valley. Darwin's daily walk of numerous rounds along this trail and into the woods provided both exercise and uninterrupted thought. He arranged a number of small stones at one place along the route so that he could kick one to the side each time he passed, allowing him to avoid interrupting his thoughts by actively counting the number of circuits he had completed that day. The Sandwalk was also a playground for his children, who would tease their father by removing stones, causing Darwin to lose count of his circuits.

Lessons from Darwin’s life and rituals

Work, Walks, and Well-Being 🥼📝🚶♂️🌳

As you can see from the above published routine, Charles Darwin's daily practices balanced focused work, family life, and health-conscious habits to offset his mental and physical health struggles. He began each day with a brisk morning walk, reinforcing his belief in the restorative power of nature. His most stimulating 'thinking walk' is followed by deep study sessions before a mid-morning break spent catching up on correspondence with his wife, Emma. Another period of concentrated work followed before he took his midday walk, thereby spending more of his day in nature.

The afternoons were set aside for leisure and family time, with long lunches, light reading, and more walks for thinking. Evenings were spent with the family, playing games and listening to music, which created a lively yet relaxed atmosphere. Despite his structured routine, Darwin often struggled with sleep, his mind ever active. His timetable reflected a way of life that combined intellectual intensity with nature, movement, and close family ties, contributing to his well-being.

Creativity and frequent breaks 💡

Charles Darwin's daily routine, consisting of three work sessions, may superficially appear minimal by modern standards in an office (however, an online survey found that the average office worker spends a considerable amount of time procrastinating during their working day, as less than 4 hours is actually spent working productively13). Yet, his typical day was marked by remarkable consistency and dedication, and, when you add correspondence and thinking time, Darwin’s routine could be seen as a very full and productive day.

This approach allowed him the freedom to explore and nurture his creativity, with time for observation and reflection. It ultimately enabled him to develop one of the most significant theories in history, highlighting the contrast with our current fast-paced, distracted lives.

Walking 🚶♀️

Scientists and authors such as Darwin, William Wordsworth, Henry David Thoreau, Charles Dickens, Ernest Hemingway, and others share a common habit of walking, which seems to stimulate their thinking14. This practice aligns with the concept of optic flow, where movement generates a flow of visual information that influences the nervous system. Some evidence suggests that walking is associated with decreased neural activity in the amygdala15, the brain area responsible for fear and anxiety16. This reduction may account for the clarity of thought and sense of relaxation frequently experienced during and following walks. Studies have also examined how walking helps with the creative process,17 with a number of participants noting that they are more creative walking than sitting. These studies encourage bouts of physical activity throughout the day for health and innovation.

Being in Nature 🌿

Like Darwin, why should we spend time in nature?

Numerous studies have examined the impact of access to natural settings on communities prone to stress and psychological pressure, including university students and those under strict lockdowns during the pandemic181920. Indeed, many studies have been conducted to understand how to optimize city/town planning for the mental health of its inhabitants. For example, Forest bathing has been encouraged by different communities around the world, most notably in Japan. Shinrin-yoku (shinrin, "forest") + (yoku, "bath, bathing") was introduced in 1982 by Tomohide Akiyama, the director of Japan's Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, who promoted shinrin-yoku as a therapeutic practice.21

The time required in nature to have significant and positive impacts on key physiological and psychological markers was revealed to be as little as 10-20 minutes of sitting or walking in nature22. Other reasons for feeling a connectedness and stabilizing effects are that walking in environments that have been there before you were born and will be there after you have gone can also have a calming effect if you feel overwhelmed by day-to-day stress. The observed effect is a reduction in stress, anger, and anxiety, accompanied by increased vigour, comfort, positive affect, and a sense of feeling refreshed.

The benefits of the different types of environments have also been examined, from untouched forests to fully designed landscapes. This includes botanical gardens, parks, grasslands, woods, waterfalls, rivers, and the coast23. Incredibly, it has also been observed that participants who watch nature documentaries tend to have lower levels of stress24. Walking, sitting in nature, or gardening are also beneficial activities25.

Focus 🎯

Darwin kept a quiet and structured life at Down House in the isolated village of Downe in Kent, 16 miles (26 km) from London. Darwin himself recognized that this may have helped his work: ‘Even ill-health, though it has annihilated several years of my life, has saved me from the distractions of society and amusement.’

Moving away from London and society to the quieter Downe helped Darwin complete his thesis. He reduced the amount of worry about attending meetings and engagements. Further, it was reported that Darwin would retire early if he did not want to socialise with visitors to Down House, with many visitors being discouraged from visiting. This aligns with many self-help productivity books, such as the ‘4-Hour Work Week’26 and ‘Deep Work’27, about how to limit distractions and to look at your schedule to remove unnecessary meetings and interactions.

Relationships and Community 💕

Ultimately, Darwin’s relationships with his family and mentors were beneficial. Darwin prioritized time with his wife and ten children and maintained correspondence with respected colleagues and friends. Maintaining social relationships and having someone to lean on who understands our struggles and goals can be very comforting and supportive, providing us with the strength to persevere and reach our goals.

TLDR: How can we incorporate Darwin’s routine into our day?

Charles Darwin's daily routine exemplifies the harmony between solitary reflection, family ties, and the restorative power of nature. His structured yet relaxed approach to daily life emphasises the value of striking a balance between work, rest, and play, showing that creativity frequently thrives in a balanced existence. We can learn something practical from Darwin and apply it to our everyday routines.

Ready to rethink your routine?

We can’t all build a path, have a large estate, or have a butler to help us with our daily routines, but we can take some lessons from Darwin’s daily routine to help us structure our lives. Take inspiration from Darwin’s approach: add pockets of rest, movement, and reflection to your day. Whether it’s a short walk, a focused hour of deep work, or a mindful moment in nature, even simple changes can boost creativity and well-being.

If possible, incorporate walking in nature into your routine, such as local parks, beaches, woods, or forests.

Investigate possible natural local areas that you can explore

Touch base with loved ones regularly. People who support you in your life and give you confidence.

Incorporate frequent breaks throughout your day.

Focus on fewer things that bring you joy.

🧠🌿✨ What’s one small change you could make today to support your mind and body?

Share it in the comments or reply to this post—I’d love to hear how you’re evolving your routine.

I highly recommend visiting Down House in the southeast of England.

On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. Darwin, C. (1859) John Murray, London.

Charles Darwin. Aydon C. (2002). Constable, London. ISBN: 978-1841195674

Darwin’s Notebook. The life, times and discoveries of Charles Robert Darwin. Clements, J. (2009). The History Press Ltd, Cheltenham. ISBN: 978-0752454948

Hayman J, Finsterer J. Diagnoses for Charles Darwin's Illness: A Wealth of Inaccurate Differential Diagnoses. Cureus. 2022 Nov 30;14(11):e32065. doi: 10.7759/cureus.32065.

Heyse-Moore L. Charles Darwin's (1809-1882) illness - the role of post-traumatic stress disorder. J Med Biogr. 2019 Feb;27(1):13-25. doi: 10.1177/0967772014555291. Epub 2016 Sep 15.

Hayman J, Finsterer J. Charles Darwin's Mitochondrial Disorder: Possible Neuroendocrine Involvement. Cureus. 2021 Dec 25;13(12):e20689. doi:10.7759/cureus.20689.

Goldstein JH. Darwin, Chagas', mind, and body. Perspect Biol Med. 1989 Summer;32(4):586-601. doi: 10.1353/pbm.1989.0038.

Young DA. Darwin's illness and systemic lupus erythematosus. Notes Rec R Soc Lond. 1997 Jan;51(1):77-86. doi: 10.1098/rsnr.1997.0007.

Field EJ. Darwin's illness. Lancet. 1990 Sep 29;336(8718):826. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93303-7.

Finsterer J, Hayman J. Mitochondrial disorder caused Charles Darwin's cyclic vomiting syndrome. Int J Gen Med. 2014 Jan 8;7:59-70. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S54846.

Darwin's bad days. Darwin Correspondence Project https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/darwins-bad-days

Charles Darwin And The Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day. Krulwich R. Krulwich Wonders blog. 2012 https://www.npr.org/sections/krulwich/2012/10/18/163181524/charles-darwin-and-the-terrible-horrible-no-good-very-bad-day

Nearly half of workers say they work 4 hours a day. Callahan C. (2023) Talent:WorkLife Newsletter https://www.worklife.news/talent/hours-in-workday/#:~:text=A%20similar%20study%20by%20career,to%20complete%20their%20daily%20work.

Hemingway, Thoreau, Jefferson, and the Virtues of a Good Long Walk. Huffington A. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/hemingway-thoreau-jeffers_b_3837002

de Voogd LD, Kanen JW, Neville DA, Roelofs K, Fernández G, Hermans EJ. Eye-Movement Intervention Enhances Extinction via Amygdala Deactivation. J Neurosci. 2018 Oct 3;38(40):8694-8706. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0703-18.2018. Epub 2018 Sep 4

Jacob RG, Redfern MS, Furman JM. Optic flow-induced sway in anxiety disorders associated with space and motion discomfort. J Anxiety Disord,1995 9, (5):411-425. doi.org/10.1016/0887-6185(95)00021-F.

Stanford study finds walking improves creativity. Wong M. (2014) Stanford Report.

https://news.stanford.edu/stories/2014/04/walking-vs-sitting-042414

Jimenez MP, DeVille NV, Elliott EG, Schiff JE, Wilt GE, Hart JE, James P. Associations between Nature Exposure and Health: A Review of the Evidence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Apr 30;18(9):4790. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094790.

Pouso S, Borja Á, Fleming LE, Gómez-Baggethun E, White MP, Uyarra MC. Contact with blue-green spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown beneficial for mental health. Sci Total Environ. 2021 Feb 20;756:143984. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143984. Epub 2020 Nov 26.

Meredith GR, Rakow DA, Eldermire ERB, Madsen CG, Shelley SP, Sachs NA. Minimum Time Dose in Nature to Positively Impact the Mental Health of College-Aged Students, and How to Measure It: A Scoping Review. Front Psychol. 2020 Jan 14;10:2942. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02942.

Antonelli M, Barbieri G, Donelli D. Effects of forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) on levels of cortisol as a stress biomarker: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Biometeorol. 2019 Aug;63(8):1117-1134. doi: 10.1007/s00484-019-01717-x. Epub 2019 Apr 18.

Meredith GR, Rakow DA, Eldermire ERB, Madsen CG, Shelley SP, Sachs NA. Minimum Time Dose in Nature to Positively Impact the Mental Health of College-Aged Students, and How to Measure It: A Scoping Review. Front Psychol. 2020 Jan 14;10:2942. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02942.

Jimenez MP, DeVille NV, Elliott EG, Schiff JE, Wilt GE, Hart JE, James P. Associations between Nature Exposure and Health: A Review of the Evidence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Apr 30;18(9):4790. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094790.

Martin L, White MP, Hunt A, Richardson M, Pahl S, Burt J. Nature contact, nature connectedness and associations with health, wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviours. J Environ Psychol 2020 68, 101389. doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101389.

Coventry PA, Brown JE, Pervin J, Brabyn S, Pateman R, Breedvelt J, Gilbody S, Stancliffe R, McEachan R, White PL. Nature-based outdoor activities for mental and physical health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. SSM Popul Health. 2021 Oct 1;16:100934. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100934.

The 4-Hour Work Week: Escape the 9-5, Live Anywhere and Join the New Rich. Ferriss T. (2011) Vermillion, London. ISBN:978-0091929114

Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World. Newport C. (2016) Piatkus, London. ISBN:978-0349411903